American Democracy, I know you and I have had our differences in the past. I may not agree with those who sing all of your praises, who call you “leader of the free world”. With the increase of democracy and globalization, now more than ever, that sentiment rings false. American Democracy, you’re getting old. But just because you are not exceptional in every way, as some may insist you are, doesn’t mean that there aren’t things to admire about you.

The first thing you’ve done that I admire can literally be called your first (amendment.) Since 1791, your people have had the freedom to say what they feel without fear of your retribution. This was especially radical when you first came into being. Compared to other nations’ citizens, like Great Britain, the protected speech early Americans enjoyed was much more expansive. Today, as a result of hundreds of years of court determination, you continue to be the most speech-protective country in the world.

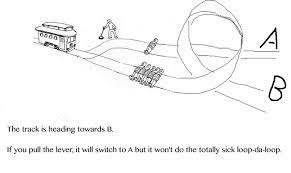

This leads into the second thing I love about you. The words of your laws, while incredibly important, are not the sole arbiter of your intentions. The Supreme Court and other court systems give your laws, rules, and regulations flexibility. You, from your very first day, have acknowledged that everything has room for interpretation. You allow yourself to change, to be argued, discussed, and revised by the people who know the most about you. For a human, this would take humility. For a country, it takes incredible foresight from its leaders.

The third thing I love about you, American Democracy, is perhaps a bit more personal. Through a series of your decisions, mistakes, and quirks, you have created one of the most vibrant arts scenes on the face of the planet. American music is a marvel. So many styles of contemporary music, like jazz, country, and hip-hop, have their roots, for better or for worse, in your decisions. Your diversity of race, religion, and location brings all sorts of people and cultures together, bringing us some of the world’s best music (and also Insane Clown Posse, but I won’t hold that against you).

America, you remind me of Shakespeare’s love from his 130th sonnet. You, too, are often “belied with false compare” by the myth of American exceptionalism. You aren’t perfect. But perfection is unrealistic, and just as Shakespeare still finds things to admire in his love, we can find things to admire in you, things much more true and admirable than any sweeping generalization could be.