This week, I had the opportunity to see a dress rehearsal for an original play called Game Night. The show, written by two high schoolers, was framed as a game show for a live audience. At certain points during the show, the audience would take out their phones and vote on plot points. While this might have been stressful anyways, the authors increased the audience’s responsibility in one key way: the audience had to choose who would die, and the characters knew it. Throughout the 50-minute production, they pleaded with the audience, whom they could not see, to spare their lives. One character had a sick sister that he had to take care of, another was just about to graduate high school and go to Harvard. One had just adopted a child with his husband, and another was a single mother of two. While I was just one member of that audience, knowing that my decision would directly impact who lived and died was an intense experience.

Going in, I told myself I’d vote in the most utilitarian way possible, make decisions that Jackson would have in this week’s article. Even though this was just a show, and the characters were just high schoolers in costume, I wanted the fewest people to be harmed. If we killed the student, it would be sad, but not as many people would be harmed as would if we killed the man who was the sole caretaker of his sister, or the single mother. Given 30 seconds to make a decision, I chose to kill both the new father and the single mother, in order to spare the student. She was the most similar to me in that situation. I felt that she deserved a chance at life. Similar emotions clouded my thinking for the rest of the performance, and all thoughts of utilitarianism went out the window.

When I talked to other audience members after the show, it became clear that lots of them also originally opted for this approach of “do-less-harm”. (Many people also just voted randomly, because they wanted to see the most interesting ending, but the nihilist vote is something I’ll cover another time.) They didn’t always vote that way, though. One person voted against the single mother because he didn’t agree with her political views, another voted to slay the brother because he was a generally unpleasant person. In the instant that we made those decisions, we weren’t thinking about the most utilitarian choice at all. Why not?

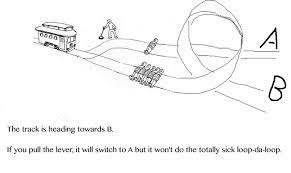

When you have time to sit and think about it, the answer to these ethical queries is clear. Don’t kill the single mother with two young kids! Switch the trolley and save five lives instead of one! Why didn’t we think of this before? We didn’t think of this before because in our discussions we’d been ignoring possibly the most important factor in how people decide things: time. We don’t have all the time in the world to make important decisions. The 30-second window will close, the trolley is going to come eventually.

Sitting in a classroom and discussing these big issues gives us that time, though, and that chance to practice these decisions, as well as to understand why other people might make different ones. An education in ethics teaches you the names of a lot of philosophers, sure, but it also gives you practice and insight. Talking about politics in school forces us to take time when we can to step back and look at the big picture. This is why classes in ethics and government are so important, and so useful.

Also, if anyone tries to get you to be an audience member for a sadistic, not-quite-legal game show? Think long and hard before you say yes.